By ZAREENA GREWAL

In the dead of night on Sept. 21, an airstrike from the skies above Mosul, Iraq, flattened the homes of my husband’s cousins, instantly killing four innocent civilians, and maiming others. The shock wave reverberated throughout our family scattered around the world, even here in quiet Connecticut.

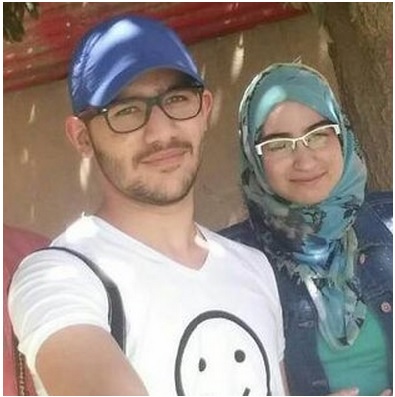

The Americanled air campaign did not hit a weapons storage facility belonging to the Islamic State, or ISIS, as one local report claimed. In a secluded part of Mosul that locals call “the Woods,” the empty government warehouse, which the Islamic State briefly occupied until January, remains untouched. Instead, the strike hit two homes nearby, killing my husband’s cousin, Mohannad Rezzo, a university professor; his 17yearold son, Najeeb; and their beloved German shepherd, Sinbul.

Mohannad’s wife, Sana, survived the explosion, which flung her, burned, from her secondfloor bedroom to the driveway below. Mohannad’s older brother, Bassim, also narrowly survived, but his wife, Miyada, and their 21 yearold daughter, Tuka, did not. Bassim’s pelvis and leg were shattered in the attack and require surgery, but it is his emotional pain that consumes him.

Meanwhile, Bassim’s elderly parents have fallen into such a state of shock and grief that they refuse to eat, and we worry for their health. As for the two families’ older children, Abdulla, Aya and Yahya, they mourn their parents and siblings from a safe distance, having moved out of Mosul last year. But like us, they are deprived of the solace of attending funerals, and are condemned to sleepless nights trying to make sense of how missiles or bombs could be launched against a defenseless family who did not have so much as a pistol in the home.

A spokeswoman for the United States Air Force Central Command confirmed that it became aware of a “civilian casualty allegation” in Mosul the day after the airstrikes. In an email Friday, the Air Force spokeswoman, Maj. Genieve David, said Centcom was assessing the credibility of the reports, before determining any followon action, which might include a “formal investigation.”

I desperately want the Islamic State to be defeated, but I wonder if our rage at it has made us blind to anyone we kill along the way, even those whose lives have been terrorized by the group.

Iraqi civilian losses used to be referred to as the inevitable “collateral damage” of war; but from the scant Arabic media coverage and the silence of the Western press, it is painfully clear that the deaths of my loved ones have not even earned that ghastly euphemism. These civilian victims are simply lumped together with the death toll of Islamic State fighters. Only one Iraqi journalist made reference to “incalculable” civilian losses in this recent wave of Mosul airstrikes.

It will not bring our relatives back, but I want their deaths to be counted and for them to be recognized for who they were: Muslim civilians, not Islamic State militants.

I visited their elegant homes, disastrously mistaken for a weapons depot. My Iraqi relatives’ lives were full of love, laughter, books, delicious smells of food, gleaming marble floors, white curtains floating in the breeze, and children running up and down the stairs. Now relatives send me pictures of unrecognizable rubble.

Last Sunday night, I sat in an airplane seat with my son in my lap, gliding past the largest moon I have ever seen, eclipsed by the slowmoving shadow of the Earth below. Like millions, I was transfixed by this glimpse of proof to the naked eye that the Earth is in motion. Seeing it was also proof that I am here, alive and able to witness such fleeting beauty. What a beautiful, terrible sign: a moon the color of blood.

As a Muslim, I believe that everything in the skies and on Earth is a sign inviting reflection. That does not mean I reject science or reason, only that I believe there is a creative, divine source of the dust that made the moon appear red. And I believe that the source of my life is also the source of my mortality. These beliefs are shared across many religious traditions, yet some insist that there is something warped, even pathological, about how Muslims understand life and death. This sustains the racist lie that for Muslims, life is cheap, that Muslims prefer death to life.

The Muslim prayer for the dead is a simple line from the Quran: “Surely we belong to God, and to God we shall return.” Muslims understand the sustenance of life, and death, as acts of God. Some take issue with Muslims’ view of the allpowerful God who creates and extinguishes life because they presume, wrongly, that this negates free will. They blame Muslims for their “fatalism,” which they argue makes God’s will an alibi for human error and corruption, and encourages Muslims to passively accept their fate and suffering.

Muslims strive for justice in this world, though we believe only divine justice is perfect. We cling to life though we know death is inevitable. The fact that some of my family members survived the airstrike by God’s mercy, and others did not, also by God’s will, does not erase the human culpability and barbarity of war, the human error that caused them to be targeted.

As we flew in that slim aluminum tube with wings, under the eclipsed moon, I felt so grateful for the blessing of the illusion that my safe arrival home was certain, that I would live to see countless full moons.

Zareena Grewal, an associate professor of American studies and religious studies at Yale University, is the author of “Islam is a Foreign Country: American Muslims and the Global Crisis of Authority” and the forthcoming “Is the Quran a Good Book?”