Few people can claim to be both accomplished painters and authors, but Maceo Montoya is one of them. As he talks to NBC Latino about his well-received recent works, he explains his visual and written creations stem from seeking and going after the “same impulse.”

Montoya was born in Elmira, California and raised in a family of Chicano artists and writers. He is the son of renowned painter Malaquías Montoya, and the nephew of the legendary late poet José Montoya. His brother, the late Andrés Montoya, was also a celebrated poet, author of the Chicano classic The Iceworker Sings.

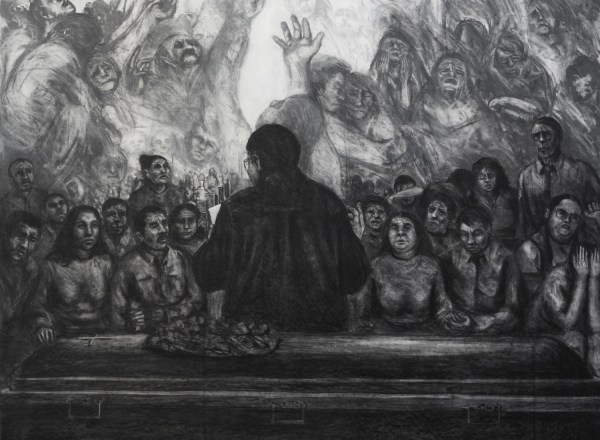

It appears that Maceo was destined to pursue a career in either the visual arts or the language arts. Maceo, however, forged his own path as both an artist and writer. His paintings grace the covers of most of his books, including the novel The Scoundrel and the Optimist(2010) and the story collectionYou Must Fight Them (2015). His second novel The Deportation of Wopper Barraza (2014) takes a humorous and innovative look at the fate of an undocumented immigrant.

He currently teaches a Chicana/o mural workshop and Chicana/o literature in the Chicana/o Studies Department at UC Davis, and his most recent project is providing the paintings for A Crown for Gumecindo (Aztlán Libre Press, 2015), a collaborative book with the Poet Laureate of San Antonio, Laurie Ann Guerrero.

The first time I heard Maceo speak he gave an amazing presentation at the tribute to the late Chicano writer José Antonio Burciaga in El Paso, TX. He read a narrative that was shaped by a slide show of his own paintings. He took a similar approach in creating Letters to the Poet from His Brother (2014), in which he merged the visual with the narrative, in this case, as a moving tribute to his brother Andrés, who died in 1999. A Crown for Gumecindo is a book of poetry Guerrero wrote to honor her late grandfather.

NBC: Guerrero writes: “praise the perfect hand of each artist, each/ perfect work, each perfect loss in every field/ we know and do not know.” For you, why is there a special connection between the visual and the narrative, particularly when it comes to navigating loss, grief and remembrance?

MM: Whether I’m writing or painting, I’m pursuing a feeling or I’m navigating through feelings. The visual simply provides one approach and the written word another, but I’m after the same thing. I don’t necessarily make distinctions, except that I’ve always felt the visual more emotionally, physically even, whereas the written word, which can begin emotionally, ends up being an intellectual understanding. In the case of loss and grief, we feel this in many ways - emotionally, physically, intellectually - and so I needed a process that incorporated this range. For me, it happens that the process involves different art forms, but I’ve always understood that they emerge from the same impulse.

NBC: Can you provide a little background about how “A Crown for Gumecindo” came to be and how you and Guerrero worked together to create this book?

MM: I first met Laurie Ann after she gave a reading in San Francisco. The year before she’d won the Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize, which is named after my late brother, so I guess that provided a natural connection. At the time, she was working through a crown of sonnets about the death of her grandfather, Gumecindo. My sense is that she was looking for ways of opening up the narrative. She first reached out to me to use details from preexisting paintings, but after reading a few of the sonnets I told her I’d be willing to come up with a new series. Laurie Ann’s poems are so visual, I feel as though the paintings were already there. But I wasn’t trying to illustrate the sonnets. Instead, I would seize upon a line, an image, and construct my own visual poem. Because Laurie Ann was still working on the sonnets, sometimes she’d send me a revised draft and I’d find that the line or image I’d been drawn to had been removed, but it didn’t seem to matter. We were after the same essence.

NBC: As both a visual artist and a writer, how do you negotiate the needs of two disciplines? Do they fight for your time or have they long come to terms with your creative process?

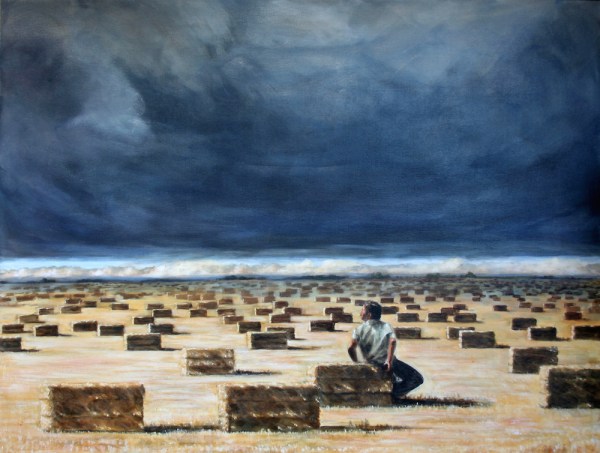

MM: I’m always fighting for time. My work in the studio has suffered most, but I can’t blame time entirely. After I finished Letters to the Poet from His Brother, which charted my development as an artist coming to terms with my brother’s death and my father’s influence, I found that I was at a loss for what to create next. I saw Letters as a bookend to a period of my life. What could I make that wasn’t a repetition of those same themes, a variation of what I’d created before? Suddenly, approaching a blank canvas, which had never before been an obstacle, was daunting. The collaboration with Laurie Ann gave me some reprieve, I think, because I was able to tap into somebody else’s emotion, but once that project was through, I returned to the same struggle. It’s not a struggle at all really, it’s just one man standing in the middle of his studio with his heart in his throat. But, damn, it’s not a good feeling.

“OUR ENVIRONMENT FORGES US, AND WHILE I DON’T WISH TO OFFER PAT EXCUSES FOR ANY SORT OF BEHAVIOR, WHAT’S INTERESTING TO ME ON THE PAGE OR ON THE CANVAS IS TAPPING INTO THAT RESERVOIR OF UNDERSTANDING, OR TRYING TO,” SAYS MONTOYA.

NBC: You’ve been extremely prolific with four books published in less than five years, but can you speak to your other role as a painter? What are you currently working on?

MM: I’m actually immersed in another hybrid project. The press For Beginners publishes graphic nonfiction and they approached me about writing and illustrating a book on the Chicano Movement. A straightforward history is a departure for me, but the visual and narrative possibilities intrigued me. Two of my favorite artists, Goya and Daumier, employed humor and satire in their illustrations while also achieving great pathos. I’m trying to channel them. I also feel a responsibility to expose a wider audience to the Chicano Movement. In every way, as an artist, writer, and educator, I stand on the shoulders of that generation of activists, and yet Chicano contributions to the civil rights movement - let alone our country as a whole - are too often overlooked.

NBC: Your other project published this year is the story collection You Must Fight Them (University of New Mexico Press), a book that looks at Chicano masculinity through a softer lens, shattering machismo stereotypes. Arguably, your paintings achieve the same result. What informs this sensitive vision as both a painter and a writer?

MM: Most families have foundational stories and in a family of storytellers mine has plenty. But there’s one that I always return to. My grandfather was an alcoholic, a philanderer, and physically abusive. When my grandmother finally left him, she insisted that her children continue to write him letters and send him holiday cards. Once, my father asked her why they did so when his father had made their lives so difficult, and my grandmother responded: “Because at one time he was a little boy just like you.”Where she found that empathy, I don’t know, but I guess it informs who I am and how I look at those around me. I search for that empathy. We don’t just exist, we’ve been created, our environment forges us, and while I don’t wish to offer pat excuses for any sort of behavior, what’s interesting to me on the page or on the canvas is tapping into that reservoir of understanding, or trying to.